All AI Models Might Be The Same

What can language model embeddings tell us about understanding whale speech and decrypting ancient texts? On the Platonic Representation Hypothesis and 'universality' in AI models

Growing up, I sometimes played a game with my friends called “Mussolini or Bread.”

It’s a guessing game, kind of like Twenty Questions. The funny name comes from the idea that, in the space of everything, ‘Mussolini’ and ‘bread’ are about as far away from each other as you can get.

One round might go like this:

Is it closer to Mussolini or bread? Mussolini.

Is it closer to Mussolini or David Beckham? Uhh, I guess Mussolini. (Ok, they’re definitely thinking of a person.)

Is it closer to Mussolini or Bill Clinton? Bill Clinton.

Is it closer to Bill Clinton or Pelé? Bill Clinton, I think.

Is it closer to Bill Clinton or Grace Hopper? Grace Hopper.

Is it closer to Grace Hopper or Richard Hamming? Richard Hamming.

Is it closer to Richard Hamming or Claude Shannon? You got it, I was thinking of Claude Shannon.

Hopefully you get the point. By successively narrowing down the space of possible things or people, we’re able to guess almost anything.

How is this game possible? Mussolini or Bread only works because you and I have a shared sense of semantics. Before we played this game, we never talked about whether Claude Shannon is semantically ‘closer’ to Mussolini or Beckham. We never even talked about what it means for two things to be ‘close’, even, or agreed on rules to the game.

As you might imagine, the edge cases in M or B can be controversial. But I’ve played this game with many people and people tend to “just get it” on their first try. How is that possible?

A universal sense of semantics

One explanation for why this game works is that there is only one way in which things are related, and this comes from the underlying world we live in. Put another way, our brains build up complicated models of the world in which we live, and the model of the world that my brain relies on is very similar to the one in yours. In fact, our brains’ models of the world are so similar that we can narrow down almost any concept by successively refining the questions we ask, a-la Mussolini or Bread.

Let’s try to explain this through the lens of compression. One perspective on AI is that we’re just learning to compress all the data in the world. In fact, the task of language modeling (predicting the next word) can be seen as a compression task, ever since Shannon’s source coding theorem formalized the relationship between probability distributions and compression algorithms.

In recent years, we’ve developed much more accurate probability distributions of the world; this turned out to be easy, since bigger and bigger language models give us better and better probability distributions.

And with better probability distributions comes better compression. In practice, we find that a model that can compress real data better knows more about the world. And thus there is a duality between compression and intelligence. Compression is intelligence. Some have even said compression may be the way to AGI. Ilya gave a famously incomprehensible talk about the connections between intelligence and compression.

Last year some folks at DeepMind wrote a paper simply titled Language Modeling Is Compression and actually tested different language models’ ability to compress various data modalities. Across the board, they found that smarter language models are better compressors. (Of course, this is what we’d expect, given the source coding theorem.)

And learning to compress is exactly how models end up generalizing. Some of our recent work has analyzed models’ compression behavior in the limit of training: we train models for infinitely long on datasets of varying size.

When a model can fit the training dataset perfectly (left side of both graphs) we see that it memorizes data really well, and totally fails to generalize. But when the dataset gets too big, and the model can no longer fit all of the data in its parameters, it’s forced to “combine” information from multiple datapoints in order to get the best training loss. This is where generalization occurs.

And the central idea I’ll push here is that when generalization occurs, it usually occurs in the same way, even within different models. From the compression perspective, under a given architecture and within a fixed number of parameters, there is only one way to compress the data well. This sounds like a crazy idea–and it is– but across different domains and models, there turns out to be a lot of evidence for this phenomenon.

The Platonic Representation Hypothesis

So how can different models be learning the shared representations? Given the massive number of ~equivalent ways in which a model can represent things, why should two models ever converge to analogous representations?

Remember what these models are really doing is modeling the relationships between things in the world. In some sense there’s only one correct way to model things, and that’s the true model, the one that perfectly reflects the reality in which we live. Perhaps an infinitely large model with infinite training data would be a perfect simulator of the world itself.

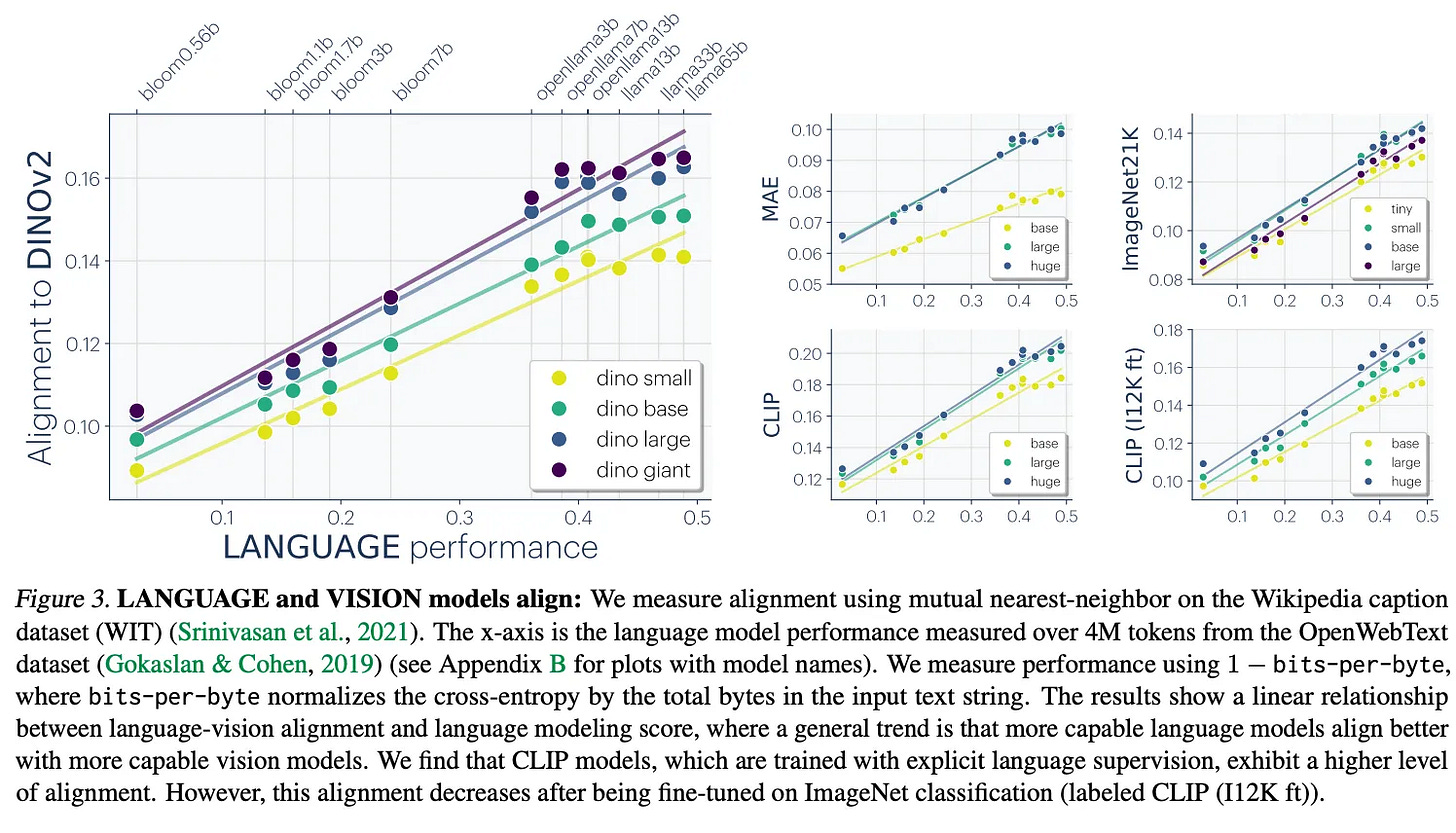

As models have gotten bigger, their similarities have become more apparent. The theory that models are converging to a shared underlying representation space was formalized in The Platonic Representation Hypothesis, a position paper written by a group of MIT researchers in 2024.

The Platonic Representation Hypothesis argues that models are converging to a shared representation space, and this is becoming more true as we make models bigger and smarter. This is true in text and language, at a minimum,

Remember the trends in scaling show that models are getting all three of bigger, smarter, and more efficient every year. That means that we can expect models to get more similar, too, as the years go on.

A brief aside on embedding inversion

The evidence for the Platonic Representation Hypothesis is compelling. But is it useful? Before I explain how to take advantage of the PRH, I have to give a bit of background on a problem of embedding inversion.

I worked for a year or so of my PhD on this problem: given a representation vector from a neural network, can we infer what text was inputted to the network?

We thought inversion should be possible because results on ImageNet showed that they could do very effective reconstruction given only a model’s output of 1000 class probabilities. This is extremely unintuitive. Apparently knowing that an image is 0.0001% parakeet and 0.0017% baboon is useful enough to infer not only the true class but lots of irrelevant information like facial structure, pose, and background details.

In the realm of text, the problem looks easy on its face, because typical embedding vectors have ~1000 floating-point numbers in them, or around 16 KB of data. If you store 16KB of text, it can represent quite a lot. Since we were working with datapoints on the level of long sentences or short documents, it seemed reasonable that we would be able to do inversion quite well.

But it turns out to be really hard. This mostly comes about because embeddings are in some sense extremely compressed: since similar texts have similar embeddings, it becomes very difficult to distinguish between two embeddings that represent similar-but-different data. So our models could output something close to the embedding, but almost never the exactly-correct text.

We ended up getting around this problem by using a primitive form of test-time compute: we made many queries to the embedding space and built a model that could “narrow down” the true text by iteratively improving itself in embedding space. Our system looks kind of like a learned optimizer that takes text-based steps to move position in embedding space.

This new approach turns out to work very well. Given an embedding model, we were able to invert text at the level of a long sentence with 94% exact accuracy.

Harnessing Plato for embedding inversion

We were very pleased with ourselves after making that method work. This had a whole lot of implications for the new model of the vector database: sharing vectors, apparently, is equivalent to sharing the text those vectors represent.

But unfortunately our method was embedding-specific. It wasn’t clear that it could transfer to future embedding models or private fine-tunes that we didn’t have access to. And it required making a lot of queries to the embedding model we knew: training the models took millions of embeddings.

We thought that this shouldn’t be the case. If the Platonic Representation Hypothesis is true, and different models (in some sense) are learning the same thing, we should be able to build one universal embedding inverter and use it for any kind of model. This idea set us off on a multi-year quest to “harness” the PRH and build a universal embedding inverter.

We started by expressing our problem as a mathematical one. Given a bunch of embeddings from model A, and a bunch of embeddings from model B, can we learn to map from A→B (or B→A)?

Importantly, we don’t have any correspondence, i.e. pairs of texts with representations in both A and B. That’s why this problem is hard. We want to learn to align the spaces of A and B in some way so that we can ‘magically’ learn how to convert between their spaces.

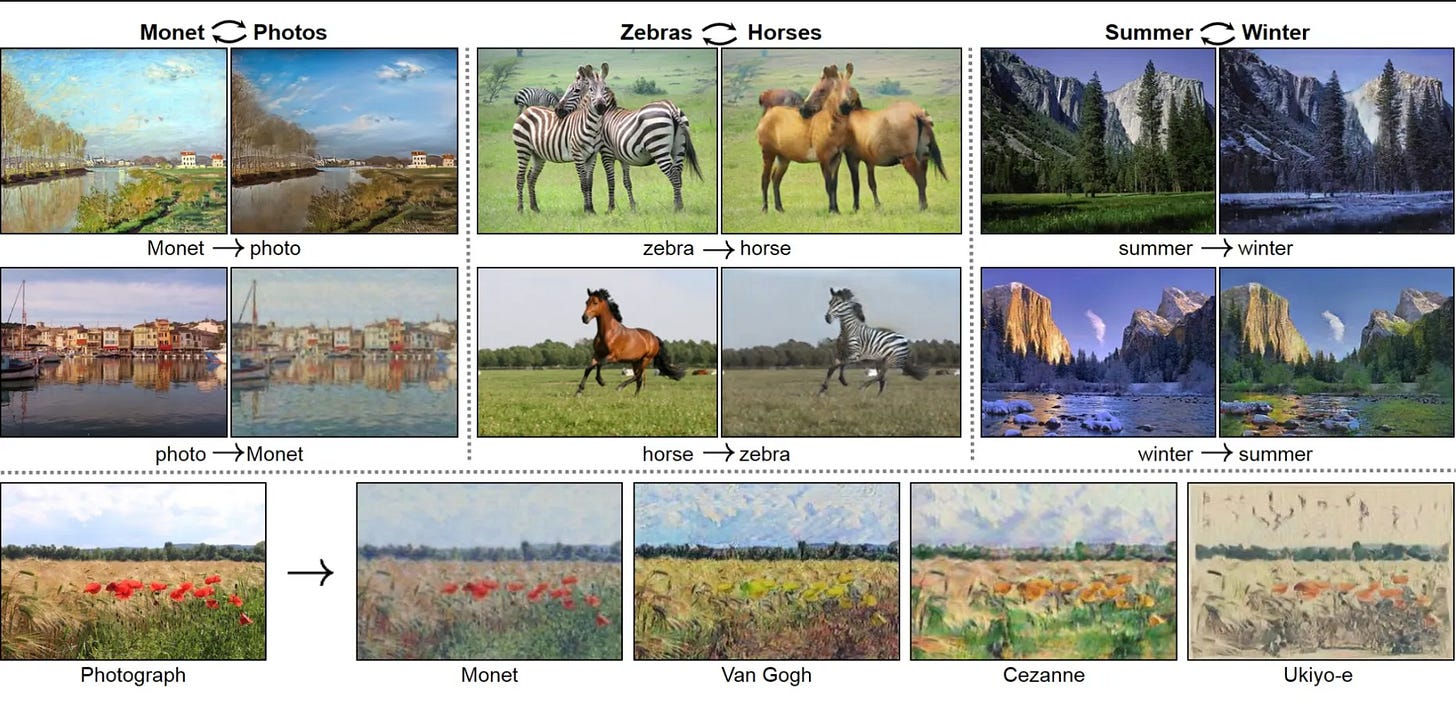

We realized after a while that this problem has been solved at least once in the deep learning world: work on a model called CycleGAN proposed a way to translate between spaces without correspondence using a method called cycle consistency:

Just imagine that the horses and zebras above are a piece of text from model A being translated into the space of model B and back. If this works for zebras and horses, why shouldn’t it work for text?

And, after at least a year of ruthlessly debugging our own embedding-specific version of CycleGAN, we started to see signs of life. In our unsupervised matching task we started to produce GIFs like this:

To us, this was an incredible step forward, and proof for an even stronger claim we call the “Strong Platonic Representation Hypothesis”. Models’ representations share so much structure that we can translate between them, even without having knowledge of individual points in either of the spaces. This meant that we could do unsupervised conversion between models, as well as invert embeddings mined from databases where we know nothing about the underlying model.

Universality in Circuits

Some additional evidence for the PRH comes from the world of mechanistic interpretability, where researchers attempt to reverse-engineer the inner workings of models. Work on Circuits in 2020 found very similar functionalities in very different models:

More recently, there’s been some action around a method for feature discretization known as sparse autoencoders (SAEs). SAEs take a bunch of embeddings and learn a dictionary of interpretable features that can reproduce those embeddings with minimal loss.

Many are observing that if you train SAEs on two different models, they often learn many of the same features. There’s even been some recent work on ‘unsupervised concept discovery’, a suite of methods that can compare two SAEs to find feature overlap:

Since the PRH conjectures that models become more aligned as they get stronger, I suspect this type of common circuit discovery will only grow more common.

What can we make of all this?

Besides being a deep philosophical idea, the Platonic Representation Hypothesis turns out to be an important practical insight with real-world implications. As the mechanistic interpretability community develops better tools for reverse-engineering models, I expect them to find more and more similarities; as models get bigger, this will become more common.

As for our method (vec2vec), we found strong evidence, but things are still brittle. It seems clear that we can learn an unsupervised mapping between text-based models that are trained on the Internet, as well as CLIP-like image-text embeddings.

It’s not obvious whether we can map between languages with high fidelity. If this turns out to be true, we may be able to decode ancient texts such as Linear A or convert whale speech back to a human language. Only time will tell.

Grateful for this read, which introduced me to the convergent representation hypothesis. I'm a neuroscience instrumentation engineer, not a computer scientist, and I've been following closely the developments in compressive sensing because I think these ideas may be important to brain recording. Anyway, I'm not sure I grasp your final point, or how these ideas relate--you suggest that we can hope to decode the few samples of Linear A we have by leveraging an otherwise complete corpus of language embeddings? At some point, the limited amount of Linear A we have still makes this a very hard inversion problem. (Luckily we can continue to record the whales...)

There are several advantages to using word embeddings instead of character embeddings when training a deep neural network. First, word embeddings provide a higher level of abstraction than character embeddings. This allows the network to learn the relationships between words, rather than the individual characters that make up those words. This can lead to improved performance on tasks such as language modeling and machine translation.

Second, word embeddings are typically much smaller than character embeddings. This is because each word is represented by a single vector, rather than a vector for each character in the word. This can make training faster and more efficient.

Third, word embeddings are already available for many languages, which can save time when training a new model.

There are also some disadvantages to using word embeddings. One is that they can be less accurate than character embeddings, especially for rare words. Another is that they can be less effective for tasks that require understanding of the syntactic structure of a sentence, such as parsing.